It’s easy, of course, to underestimate the weight of a baby. The average birth weight these days is over 7 pounds, and by the time the baby is 4 months old, it might be double that. If the baby were a bowling ball—professional bowler weight—it would seem quite heavy. A 4-month-old weighs about the same as a 2-gallon container of water. It’s easy to see how someone lifting and moving that kind of weight can get sore. But they are moving that object with considerably more care than they might a plastic jug of water or a bowling ball. The muscle tension required for fine movement control while holding on to a heavy weight puts an enormous strain on the whole mechanical system. Some muscles of the body seem well designed to handle massive enlargement and strengthening if circumstances required it. Biceps and shoulders, and the muscles of running and leg movement are good examples. Except for a protective covering of skin, they have a good blood supply and can pretty much expand from exercise to whatever size is needed. Though we’ve all seen photos of shockingly-massive bodybuilders, much of the muscle size they have is in these muscle groups. The fact that babies are considerably more adorable than, for example, steel weights, gives us the motivation to keep picking them up. Weightlifters, however, are not looking to build up or enlarge those fine-motor muscles, which are usually invisible even in the most defined physique.

The wrist problem occurs because those fine-control muscles, of the hand and fingers and forearm, are threaded though a remarkable system of lubricated sheaths to keep everything operating smoothly. They are threaded through notches to keep them from tangling or getting caught on angles of our bones and joints, and they slip through guide-channels so that they don’t restrict the range of motion of our joints. With enough repeated exercise, just like lifting a barbell, those little muscles get stronger—and bigger. If they get even a little too big, they start rubbing the inside of the sheath they pass through, they rub against each other, and they don’t slide as easily through their notches. This leads to irritation, inflammation, and pain. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome is the best known of these, but there are others. Treatment is simple, if inconvenient with a baby around. Immobilize the problem area, ice if possible, and anti-inflammatory medicine like ibuprofen.

This leads to the important question of this post. The same question has come up before and probably will again. What, exactly , is my job?

I’ve worked in other practices where the pediatrician’s job is reasonably clear. Since I was paid a fixed salary and the practice was paid a fixed price per visit, there was constant pressure from management or the owner/partners to do as many visits as possible. There was never any kind of incentive, even appreciation, for doing a good job, being thorough, ending a visit without the child screaming and traumatized.

When I started my own practice, I wanted to do things differently. I knew, of course, that the business model of the factory-production design of medical-care delivery was the way a doctor could earn a living. There are some really good reasons that nobody else practices the way I do. Still, I wanted to have the feeling of taking care of kids and dealing with the whole person.

That sounds great, but it is so different from my training and experience that some really confusing issues have come up. In the 8-minute pediatric visit, the doctor has decided that your kid’s upset stomach is from a virus and not appendicitis, tells you to keep up with fluids, and has left. That, to be blunt, is the standard of care. Teasing out the history of stomach aches, the recent weight loss, and a recent history of food refusal could take an hour, especially if the doctor actually tries to ask the child. And what about symptoms in the parents? These could hold an important clue to what could be going on in a child.

Where does my care of the child end and care for the parent begin? All of my insight about postpartum depression stems from my belief that it’s not all about the mother. It’s the mother-baby system that somehow isn’t working optimally. Helping the mother is de facto helping the baby, who is indeed my patient. In the same way, I would strongly urge any parent to wear a bicycle helmet. My patient needs you. Without a head injury.

Which leads to the case at hand. A mother, mid-30’s, was in today with her baby. The baby was fine, but mother was wearing black neoprene wrist supports. I asked what was going on. She said that she had been having wrist pain and went to her doctor, who told her she had carpal tunnel syndrome. Here’s where my role gets confusing. What could she be doing that could give her carpal tunnel syndrome in both wrists at the same time? I didn’t think she was working in a parts-assembly factory or on a computer since the baby was born 3 weeks ago. She wasn’t, she confirmed, and after asking her a few more questions, it was clear that this wasn’t carpal tunnel. Do I tell her her doctor was wrong?

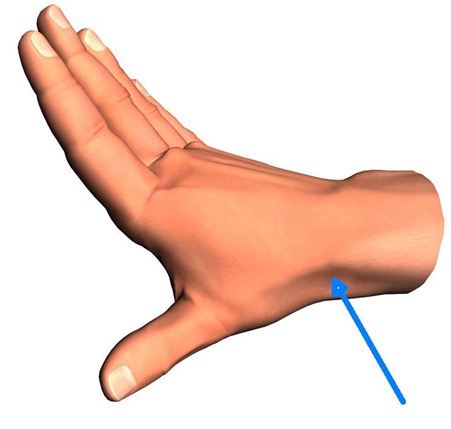

She pointed to where it hurt, which was the same on both left and right. Uh, that’s not where carpal tunnel hurts. It wasn’t where nursemaid’s wrist hurts, either, and that was what I had been thinking. I touched where she said it hurt, and she confirmed a little bit of pain. I asked her to hold her hand bent in a certain way, then I pressed her thumb across her palm. This hurt a little, too. In this position, I pressed on the spot pointed out by the arrow in the picture above. She jumped. This was the Finkelstein Test—I’m not making that up. I know, it sounds like an algebra mid-term from high school. (He published this in the late 19th-century, I think.) Her reaction led me to her diagnosis.

DeQuervain’s Tenosynovitis isn’t something that people assume they have. It occurs mostly in women, mostly in their 30’s and 40’s. It is thought that long before Dr. DeQuervain stuck his name to it more than 100 years ago, it was known as mother’s wrist.

If a little knowledge is a dangerous thing, what about knowing about the Finkelstein Test? I suppose it would be right to say I couldn’t be positive about her diagnosis, but I was pretty sure this is what she had.

Here are some of the issues for me as a physician:

- I’m not a doctor for grown-ups. Do I mind my own business even if I think I’ve got a clue—and maybe they don’t?

- Do I say something cautious like, ‘Maybe you should get another opinion.’ Isn’t my opinion another opinion?

- If I say, ‘Have you looked into DeQuervain’s Tenosynovitis? It’s going around,’ what is the message I’m really sending?

- If I say, ‘I believe you have DeQuervain’s Tenosynovitis,’ what is my next obligation? Do I have to treat it or suggest treatment?

- What if I’m wrong?

- How much work do I have to do, especially since I can’t get paid for any of it? Officially, the mother is not my patient.

- Since I was bold enough to bring up the fact that I can’t get paid anything for diagnosing or treating the mother, it’s obvious that this fact doesn’t reduce my potential liability.

Let me go one step further. If I know the diagnosis, if I can help this woman’s suffering, don’t I have some sort of obligation to help? Am I required to look the other way because of my contract with her health-insurer? In this case, of course, there isn’t anything life-threatening that would meet the criteria of what any reasonable person would do. This comes up, for example, when somebody is obviously gravely hurt and anybody—not just a doctor—would call for help.

Do you think I’ll leave it at that? I didn’t think so. This case is a proxy for treating even my own patients for mental health problems. Though child mental health care (and to a lesser extent adult mental health, as well), is usually either completely unavailable or nearly unavailable; though it is unaffordable if available; and though access to it is severely limited by health insurance, physicians are generally precluded from providing this care. So even though I’m willing to do it, I do a good job—especially with certain problems, I’m available and I’m willing to take about 20-30% of what they would usually have to pay, insurance companies will not pay me to diagnose and treat most mental-health problems. Some won’t even let me prescribe the appropriate medications. (I can prescribe them, but they won’t pay for them.)

And it’s a proxy for the inadequate recognition and treatment of postpartum depression. This is seen by me, diagnosed by me, treated by me. I get paid nothing for this, yet there’s no one to whom I can refer these women. I’m lucky that one of the authorities in the field is nearby and will take referrals—without taking insurance. After her, however, it’s me.

Just because I make no secret of believing I should be paid for my work doesn’t mean I won’t do what’s required of me. By me. So I had to create my own practice where the family of the baby got what it needed for the benefit of the baby. That, in the big picture, is Holistic Medicine.

I found some information on DeQuervain’s Tenosynovitis on the internet and printed it out for her. Treatment required a completely different kind of splint, which I also described. I don’t know the name of her doctor and didn’t ask who it was. But I deeply suspect that there were only a couple of reasons that she was still suffering in pain. Either the doctor didn’t know about this unusual diagnosis, or didn’t listen carefully enough to the patient. It was in her description of the the problem, the timing of its onset, and the exact location of the pain that eliminated diagnostic possibilities like carpal tunnel syndrome. I think these are both potential problems: a doctor who doesn’t know or a doctor who doesn’t listen. Nobody can know everything, and this is an unrealistic goal. But it would be great if doctors would spend the time to listen carefully, and then be open about not knowing. When that happens, good doctors hit the books.

As a closing aside, this is an ongoing pattern in Every Patient Tells a Story, a book about unusual diagnoses that I like a lot and reviewed in this blog a while ago. Though the author was kind about it, the first doctor to see these unusual problems often didn’t make a correct diagnosis. But at some point, all the patients described finally saw a professional who wouldn’t give up, even if they didn’t know. They reasoned it out, did what homework was needed, and got to the diagnosis. Of course, they weren’t paid more for this extra work than the doctor who said, because it would take the least time, ‘carpal tunnel syndrome.’